Modern society treats time as a straight line. Minutes tick forward, deadlines loom, court cases drag on, news cycles move relentlessly from outrage to amnesia. We behave as though time is neutral, mechanical, and obedient to calendars and clocks.

That idea, however, is historically shallow—and scientifically wrong.

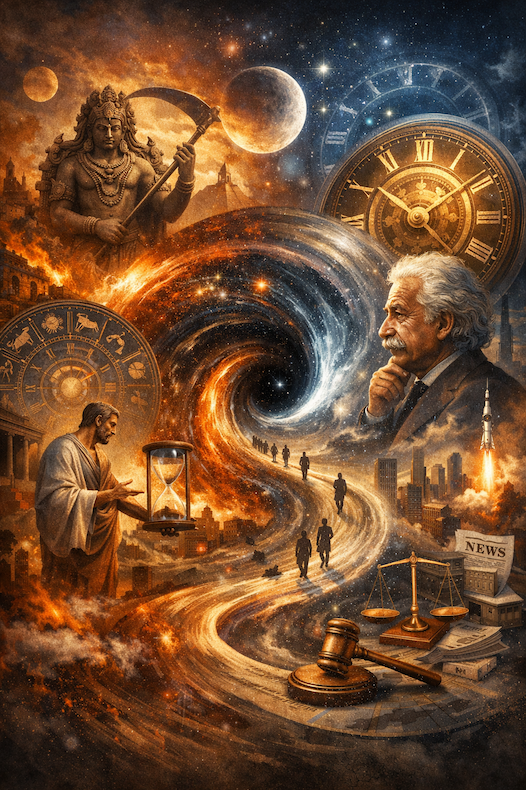

Long before physics caught up, ancient civilizations understood something we are only now relearning: time is not a line; it is a force.

In ancient Indian thought, kāla was not merely time but a cosmic principle—cyclical, destructive, creative, and moral. Time did not simply pass; it acted. Empires rose and fell because their time had ripened or expired. Justice delayed was not neutral; it altered the moral fabric of the world.

The Greeks made a similar distinction. Chronos was measurable time—the ticking clock. But Kairos was decisive time: the moment when action mattered, when delay became failure, when opportunity closed. One could miss Kairos even while Chronos marched on faithfully.

These were not mystical abstractions. They were frameworks for governance, war, justice, and memory.

Then came the modern age—and with it, the illusion that time could be standardized, mastered, and stripped of meaning. Newtonian physics reinforced the idea of absolute time: the same everywhere, for everyone, regardless of circumstance. The clock became king.

That illusion collapsed in the early 20th century.

When Albert Einstein introduced the theory of relativity, he didn’t just revise physics—he quietly validated the ancients. Time, Einstein showed, is not universal. It stretches, slows, and bends depending on motion, gravity, and perspective. There is no single “now.” Two observers can experience the same event in different temporal realities—and both can be right.

What ancient philosophers sensed intuitively, Einstein proved mathematically: time is relational.

Yet here’s the irony. While science has moved beyond absolute time, our institutions have not.

In law, politics, media, and public affairs, time is still treated as if it were neutral—when in fact it is weaponized. Delays exhaust public memory. Speed overwhelms scrutiny. Long legal timelines quietly favour those with resources, while communities trapped in slow time suffer consequences that never quite reach closure.

A disaster does not end when headlines fade. For affected communities, time stretches. For insurers and corporations, time contracts into procedural milestones. For the public, time dissolves into distraction. These are not failures of attention—they are failures to understand that time itself has unequal weight.

The ancients warned us about this. Kairos ignored becomes catastrophe. Kāla denied becomes decay.

Einstein, too, offered an uncomfortable truth: if time is part of the system, then how we structure systems determines how justice, memory, and responsibility unfold. Time does not merely reveal outcomes; it shapes them.

Perhaps the most unsettling implication of relativity is the idea that past, present, and future coexist—that events are not gone, only located elsewhere in spacetime. Ancient cultures believed something similar: that the past is never dead, only dormant, awaiting recognition.

If that is true, then unresolved histories, delayed accountability, and postponed reckoning do not disappear. They accumulate mass. And like gravity, they eventually bend everything around them. The mistake of our age is not that we lack technology or data. It is that we still think time will absolve our sins.

The ancients knew better. Einstein proved them right. Time does not heal all wounds.Time remembers. And sooner or later, it demands its due.